Uncompromising discipline on crime is a must to merit the Republican nomination.

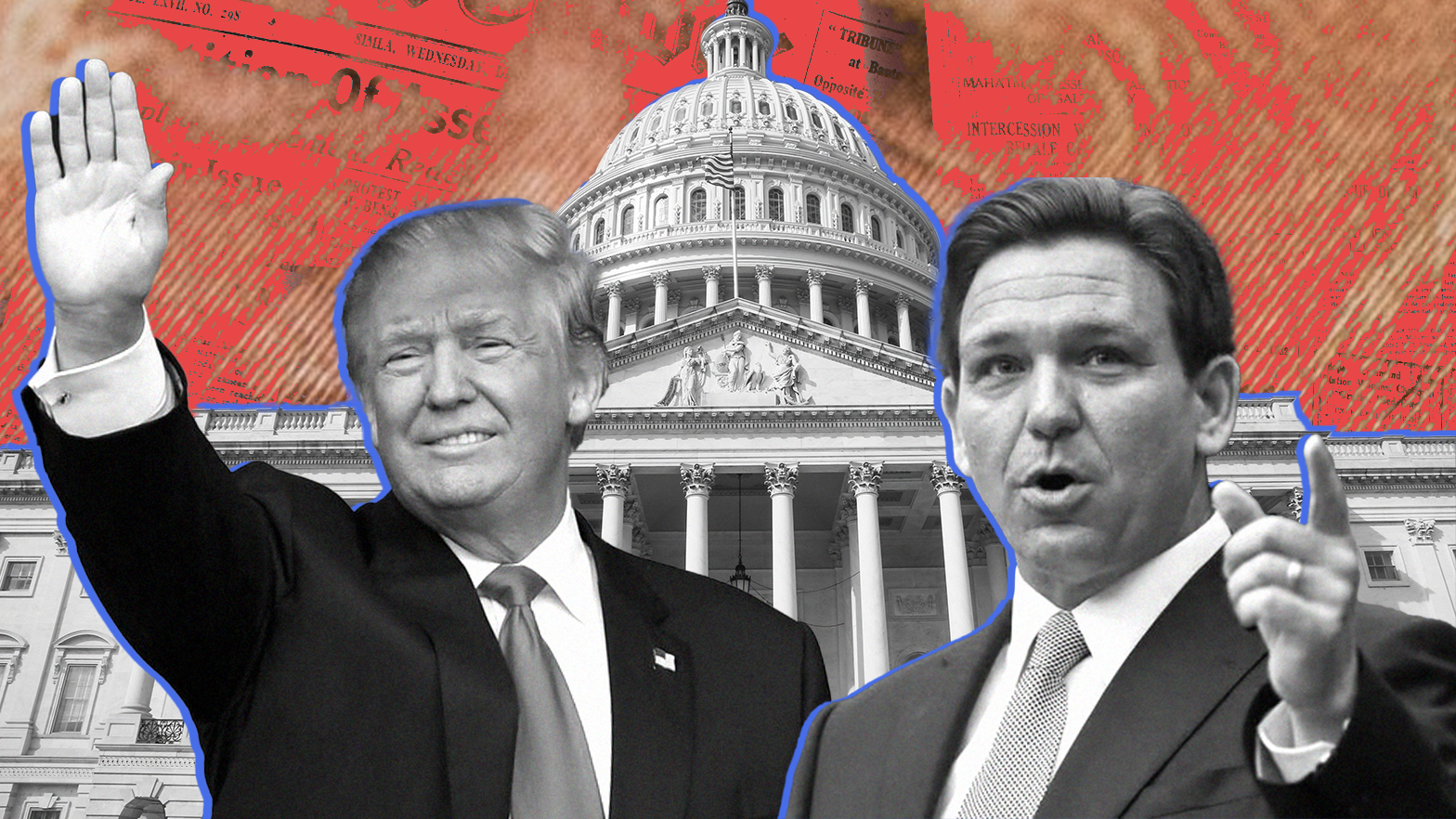

The Practical Case Against Trump 2024

We cannot afford a repeat performance.

As conservatives mull Donald Trump’s return to electoral politics, some will see Trump’s temperament and character as disqualifying. Others may be swayed by indignation at the injustices suffered by Trump at the hands of the Democrats, the media, and the FBI, satisfaction at the way Trump works overtime to “own the libs,” or an understandable longing to return to the days of $2.00-a gallon gasoline and a president not suffering signs of dementia.

Conservatives, however, cannot afford to get 2024 wrong. There is simply too much at stake. If they want to meet the challenges of woke authoritarianism, hyper-centralization, and fiscal insolvency at home and aggressively hostile nations growing stronger abroad, they have an obligation to their country to apply cold, hard reason to the question. Even those with sympathetic feelings toward the former president must be concerned with two practical questions: Would Trump win? And would he be effective if he did win?

Trump 2024: Tired of Winning?

The former president’s defenders will argue that he has won already (at least) once. There are strong reasons, however, to doubt that he will repeat the performance. Overall, Trump won 45.9% of the national vote in 2016 and 46.8% in 2020. In 2016 Trump faced propitious circumstances as a challenger—an unpopular opponent seeking a rare third consecutive term for her party, when three out of five voters thought the country was headed in the wrong direction. In 2020, he faced unpropitious circumstances as an incumbent—a better-liked opponent, riots, recession, and pandemic, when more than three out of five voters thought the country was headed in the wrong direction. The results were nearly identical. It is fair to surmise that Trump faces an effective electoral ceiling of around 47%, regardless of national circumstances and the identity of his opponent. This does not guarantee he cannot win, since (as in 2016) he could eke out bare pluralities in enough crucial states to attain an electoral college majority. But his path will be quite narrow, and he will be starting at a serious disadvantage, as current favorability polls suggest. And of course, there is no guarantee that Democrats will put Biden up again rather than someone with fewer weaknesses.

One must also consider the prospective dynamics of a race featuring Trump as the 2024 Republican nominee. Unless there is a dramatic improvement in the national condition in the next two years, the incumbent party will carry a heavy load with or without Biden as its candidate. Normally, this would be a perfect opportunity for the challenging party to run a campaign focused on the incumbent party’s failures. The challenger could and should offer a positive alternative but would seek to make the election a referendum on the incumbent party’s stewardship.

Trump as the Republican nominee would upend this strategy. If he remains true to form, he will focus on his own grievances. He will complain about Democratic inflation and destructive education policies, but obsession with The Steal and disloyal Republicans may drown out all else. The voters in the middle—the ones who were alienated by Trump in 2020 and who will decide the race in 2024—do not share Trump’s obsessions, a fact borne out in the midterm elections. As importantly, Trump will have his own record to defend. Rather than a contest around the question of whether the country can stand four more years of Democratic misrule, there will be a contest between two competing and problematic legacies. A repudiated president will not be the most effective messenger for a campaign that must center on holding the incumbent party accountable. Trump will be subject to a barrage of 30-second ads reminding voters about early COVID missteps, January 6, and Trump’s praise for the intellectual acumen of Vladimir Putin. Democrats may be about to hand Republicans their best opportunity since 1980. Is Trump the candidate best positioned to take advantage of it? It seems unlikely. Indeed, there is considerable evidence that Republicans failed to take advantage of their 2022 opportunity largely because the election became less a referendum on Biden than another contest between Biden and Trump.

Another Trump Administration?

The second key question is whether Trump, if he squeaks by, would be the most effective president Republicans can offer the country. There are very good reasons to doubt this as well, starting with the fact that Republicans have a number of very solid prospects from whom to choose. Ron DeSantis is an experienced, effective executive who has turned a swing state into a GOP bastion; Mike Pence, Mike Pompeo, Tim Scott, Glenn Youngkin, and Nikki Haley are also credible potential presidents.

In comparison, Trump would enter office on January 20, 2025 with several serious disabilities. First, he will be nearly 80. The disadvantages of a superannuated president are already apparent. (This might also prove to be an electoral weakness, not just a governing weakness, if Democrats ditch Biden and nominate someone younger.) Second, if Trump wins another victory in the electoral college while trailing by millions in the nationally-aggregated popular vote, he will immediately take office once again under the political disability of being a minority president. Pressures to change or abolish the Electoral College, as destructive as that would be, would likely grow. Another Republican candidate may also win this way, but it is almost certainly the only way Trump could win. Third, he will enjoy no honeymoon, no benefit of the doubt. Finally, the 22nd Amendment would make Trump a lame duck president from the beginning, and Republicans would forfeit the powerful advantage of presidential incumbency in 2028 that they would normally have earned by winning in 2024.

Trump’s 47% electoral ceiling translated to a 47% ceiling in job performance ratings throughout his presidency. In fact, his RealClearPolitics average approval ratings were underwater—disapproval exceeding approval—for his entire presidency after his first week in the White House. Most of the time, his approval was in the low 40% range, even when the economy was roaring. Is there any reason to believe he will do better the second time around? Does he seem likely to learn useful lessons from his first term? Like a second marriage, throwing the dice on a second Trump presidency would require the triumph of hope over experience.

One can summarize that experience from a conservative perspective.

As leader of the executive branch, he was moderately successful at restraining new regulation but otherwise left dozens of key positions open for years and suffered from unprecedented turnover. Trump often appointed good people, but few were able to endure the experience for long. And after Trump’s treatment of John Kelly, Jim Mattis, Bill Barr, and Mike Pence, who of high quality and independent mind will want to serve in the next Trump Administration?

As a legislative leader, Trump had two major successes: the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, to which he contributed little and which the Republican Congress would have passed no matter which Republican had been president, and the FIRST STEP Act, which reduced criminal sentencing. Anything else of note failed, including repealing Obamacare and finishing the border wall, two of his key promises. For the most part, Trump lacked the skills to work with Congress and was uninterested in learning them. Since so much was done through unilateral executive action rather than legislation, it took Joe Biden a matter of hours to undo it.

As a steward of the nation’s fiscal condition, Trump was an unmitigated failure. He made no significant effort to couple the tax cuts with spending restraint, and even before COVID hit, federal deficits were on a trajectory to reach $1 trillion a year.

And as Head of State, Trump was rarely able to master the art of representing the whole country. In a highly polarized setting, that is a tall order. But to succeed you first have to try, and Trump rarely tried. Mobilizing his base against real or perceived enemies was his focus. Consequently, even independent voters, who gave him a four percentage-point lead in 2016, abandoned him in 2020, when Biden won them by 13. (In 2022, Independents also turned against Trump’s allies in U.S. Senate races.) Here, Trump’s deficiencies of character were telling. Even those who do not consider those deficiencies disqualifying in themselves must consider how they affect his electability and capacity to serve effectively.

Conservatives could cheer a number of important Trump policies, including tax cuts, energy independence, a stronger border, and originalist court appointments, but most were long-time Republican commitments likely to have issued forth from any Republican president. In particular, in the wake of the reversal of Roe v. Wade, Trump should be granted the credit he is due for his Supreme Court appointments (though it cannot escape notice that he now seems to be distancing himself from the accomplishment). But does anyone think that Ron DeSantis or Glenn Youngkin would not make solid constitutionalist appointments if elected in 2024?

At the same time, Trump shares responsibility for some of today’s most troubling policy maladies to a degree his supporters rarely acknowledge.

Consider, for example, inflation. Biden put the finishing touches on our current inflation picture, and no doubt made it worse. The American Rescue Plan and our renewed dependence on foreign energy assured that. But Trump laid the foundation. His fiscal policies were completely undisciplined, and throughout his presidency, he supported the Federal Reserve Board’s loose monetary policy. When Congress passed yet another stimulus package in December 2020, Trump harshly criticized it for not being big enough. If we are awash in funny money, Trump got the printing presses warmed up for his successor.

Another major domestic trauma of the moment is crime. Here, while Democrats briefly raised the “Defund the Police” cry, Trump helped propel the deincarceration bandwagon.

Then there are events abroad, starting with the national humiliation and strategic defeat occasioned by the loss of Afghanistan. Biden cannot escape responsibility for making the final call to abandon Kabul. But Trump set the fiasco in motion. Eager to be able to say that he ended the “forever war,” he was the one who reached an agreement on U.S. withdrawal with the completely untrustworthy Taliban.

In Ukraine, Trump did more than either Barack Obama or Biden before the full-scale Russian invasion, and Vladimir Putin may well have been enticed to act in 2022 by Biden’s apparent weakness. However, that weakness was made most apparent by the Afghan disaster, in which Trump had a hand. Moreover, while Trump did more than Obama, he did less than the situation required and paid no sustained attention to it. And whatever one’s view on U.S. aid to Ukraine today, we should all be able to agree that the best scenario would have been for the Russian invasion to have been deterred to begin with. Altogether, if Americans are afflicted by rampant crime and inflation, if Afghanistan is once again governed by an enemy that was complicit in the worst terror attack in U.S. history, and if Russian imperialism is running amok, it is not for the most part because Biden reversed Trump’s policies in those areas (though he did, catastrophically, in energy and immigration).

One final feature of Trump’s presidency bears mentioning: his role as party leader. Though he was highly effective at the dubious goal of making personal loyalty to him the litmus test of who was a “good Republican,” he was not effective in building up the party. The bottom line? In 2017, when Trump took office, Republicans held the presidency, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. Four years later, they had lost the presidency, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. After four years of Trump “owning the libs,” the libs owned the country.

Conservatives cannot afford a repeat performance. Neither can America.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

And rightly so.

A time for unreasonable expectations and irrational politics.

The 2022 midterms were a blessing in disguise for the GOP.

Donald Trump, the GOP, and 2024.

Whoever wins in 2024, our problems run deeper.