A vengeful quest for social purity ends only in public ugliness.

We Control Our AI Destiny

Agnieszka Pilat’s artistic plea for using tech responsibly.

Hollywood depictions of rogue artificial intelligence (AI), ranging from Terminator to 2001: A Space Odyssey, have captured fears about the rapid pace of technological change. Lately, AI’s hilariously inaccurate depictions of historical figures, from female popes to black Vikings, has even entrenched a deep skepticism about new tech’s ability to make our lives easier.

One artist from a dystopia not so far in the past, however, disagrees with the reigning consensus. Born in Soviet Poland, Agnieszka Pilat is on a mission to show the world that humans have a responsibility to ensure that AI reflects the very best of human creativity, or risks manifesting the very dystopia imagined by Hollywood.

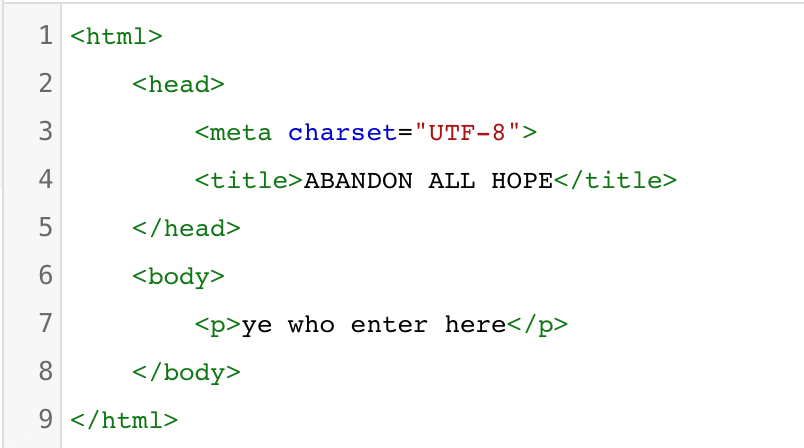

Agnieszka’s unorthodox art has been featured in The Matrix: Resurrections and is currently being exhibited in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. Her art, which is painted by three Boston Dynamics robot dogs continuously, day and night, reimagines famous works from across human history in the form of man-made material: sleek carbon fiber replaces skin, explosive rockets showcase the power of human emotion, and utilitarian robot hands reach for one another in her Augmented Reality Sistine Chapel.

When I first saw her work, I reacted the same as many do on the Right, with a mixture of curiosity, unease, and perplexity. How could an artist let a soulless machine paint her works? Wouldn’t that rob the artist and the viewer of the artist’s own vision for the piece and the creative process? What should we make of an artist willing to submit her agency to machines that create mass produced art, devoid of any uniqueness or narrative?

Agnieszka’s upbringing in Soviet Poland contained all the answers to my doubts. “Every human being is driven by values,” she remarked. In Soviet Poland, the oppressive conformity of society created what Václav Havel labeled “a world of appearances trying to pass for reality.” Public displays of obedience by Poles masked the oppression and intransigence of the ruling Communist Party. Soviet Poles “lived within the lie” of the communist system by behaving like they believed the lies or by suffering through life in silence.

This conformity deeply affected Agnieszka’s family. However, once General Jaruzelski’s communist government fell, it didn’t last. Her father’s years of drinking, caused by the suffocating repression of the Polish communist regime, evaporated. No longer a cog in the Polish Soviet machine, he proceeded to build a bakery business. “Technology has always been a democratizing force,” Agnieszka said. “The first thing my family did when the wall came down was we bought a car. That piece of technology unlocked the ability to start a business and revitalized our family.” Through her art, Agnieszka accomplishes this same mission: showing how technology can be a vital resource for humanity, if programmed and guided prudently.

“Without human agency these machines have nothing.” Agnieszka rightly points out that the coding of her General Dynamics robots is completely dependent on her own artistic skill. She notes that the controversies surrounding Google Gemini and other AI chatbots are not surprising since “everything they know is online.” These AI chatbots are the product of the engineers who built them, which is why Agnieszka stresses that technology “is not neutral, but…a tool; purely digital art just mimics what we [create] as humans.”

The robots Agnieszka uses to construct her paintings are, in a sense, her own art students. Any robot off the assembly line begins with no knowledge of Agnieszka’s art—her brushstrokes, stylistic idiosyncrasies, inspirations, or history; they don’t even recognize a blank canvas. “The robots I use, and because they’re built a certain way, they have their own language or programming. Everything I do with the robot is unique,” she explained, answering my concern that standardizing artistic styles to lines of code would mean anyone could fire up a computer, hook up a robot with an Art 101 AI, and recreate the Mona Lisa.

Pilat’s guidance, correction, and adjustment of each piece her robots create in turn refines and improves each robot’s artistic ability. Just as human beings need to practice, practice, practice, Pilat’s robots are guided with deliberate intention and commitment to improvement. What could be more human than that?

Today, the behavior of the humans behind technologies that millions of people interact with in their daily lives garners more attention than the innovative technologies themselves. In opposition to Agnieszka’s responsible utilization of modern technology stand bureaucrats like Nina Jankowicz, who led the Department of Homeland Security’s Disinformation Governance Board and denounced “free speech absolutists” taking over social media platforms.

When ideologically motivated bureaucrats exercise power over social media platforms to silence their political enemies and empower private corporations to curtail Americans’ free speech, many are rightly suspicious of further technological developments. Why celebrate AI and robotics if we can’t trust the people who control them? Agnieszka points again to technological breakthroughs that, yes, fundamentally reshaped societies and institutions, but also empowered individuals and communities.

Indeed, as Pilat remarked, “Print technology led to the Reformation and allowed people to read the Bible for themselves.” Today, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) allow those with ALS or other diseases that cause a loss in motor function to communicate with caregivers and restore a measure of independence to their lives.

Encrypted communications allowed protestors in Hong Kong to defy the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2020 and broadcast their moment outside the Great Firewall and maneuver within the technological police state. It is precisely because of her experience in Soviet Poland that Pilat believes the CCP will not be able to keep out all foreign sources of information or restrict it from within. “I am not scared of China. To build great technology needs free minds. Free minds cannot thrive in an oppressive system. I remember being in China and using encryption and private servers to talk without the government knowing.”

There is a strong sense, particularly on the American Right, that we are operating under our own technological surveillance state. Federal money has been funneled to censors at Stanford University and several NGOs for the purpose of researching and turning over data to the federal government about misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda.

The Twitter Files detailed how public health experts at Harvard, Stanford, and Oxford had their accounts restricted, limiting the number of people who saw their content. Most damning, the Twitter Files showed how the Biden campaign worked with Twitter to delete and suppress information harmful to their candidate. Yet, there have also been a proliferation of new encrypted apps like Rumble, Gab, and Signal. Substack has allowed individual journalists, students, and startup pundits to deliver content to audiences everywhere. New technology and other devices that haven’t left the drawing board yet will allow individuals to combat the tyranny of 21st century government oversight.

In many ways, the federal government has inherited the same problem the Soviet authorities had with cracking down on self-published and self-distributed underground literature known as samizdat. Shutting down one newspaper and dispersing its publishers would result in a new publication being founded overnight. The Soviets poured resources into engaging in samizdat whack-a-mole and miserably failed. Samizdat fostered new social networks and connected truth seekers with artists, writers, political dissidents, and friendly ears within the hostile regime.

AI and robots can turbocharge American samizdat. For Agnieszka, technology itself is engineered toward empowering individuals, not government. Günter Schabowski’s mistaken answer regarding whether East Germans could cross into West Germany at a press conference of East Germany’s Politburo on November 9, 1989 triggered thousands of people to pour across the Berlin Wall’s checkpoints, “shattering the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the [Communist] system” as Havel wrote. That mass mobilization wouldn’t have been possible without the television. Agnieszka agrees as much: “I would argue the wall is an old technology, the radio went over the Iron Curtain and today’s technology will not allow the government to oppress anymore.”

Technology holds plenty of promise but also unease for the future. The seemingly inevitable march toward technological totalitarianism, however, seems not so inevitable if technological development is not guided by totalitarians. The painstaking training and troubleshooting Pilat undergoes with her robot students working on a canvas is a reflection of America’s need to foster technology responsibly.

Americans have gotten glimpses of the power of technology to shape our perceptions of reality, seeing its potential devastating consequences. But Agnieszka Pilat offers a more optimistic view of technology’s future impact on human society. The technological tool that Big Tech wields can also be brandished by humane writers, artists, and activists. Like Soviet Poland, oppressive regimes that attempt to put all technological power under the state are bound to be hollowed out by the samizdat of their day.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Artists need to band together and revitalize our cratering culture.

The advertising industry is the unacknowledged legislator of wokeness.

We are rapidly becoming post-civilized.

Ruthless outsourcing will be the death of the American Dream.

Whoever wins, we’ve got work to do.