Not in America, and not anywhere else.

Populist Conservatism is What the Country Needs

Working citizens rightly rally around statesmanship, not ideology.

Colin Dueck’s essay basically nails what’s going on. Cultural and economic changes are breaking up the old political coalitions and recreating new ones across the globe. As it applies to America, that means the Republican Party is—like many of its center-right counterparts abroad—becoming less wedded to free markets, more open to economic intervention, and more serious about soothing cultural fears. There’s not much party leaders displeased with this trend can do about it, since in a two-party democracy both parties’ leaders ultimately follow the voters.

This latter statement surely sticks in the craw of many movement conservatives. In their view, conservatism represents a set of unerring, eternal truths which provide for happy, prosperous, decent societies. The political goal of the movement, in this view, is not to adapt to public sentiment; the goal is to change sentiment. Political adaptations such as that envisioned by advocates of a conservative populism are, according to this view, unprincipled and hence unconservative.

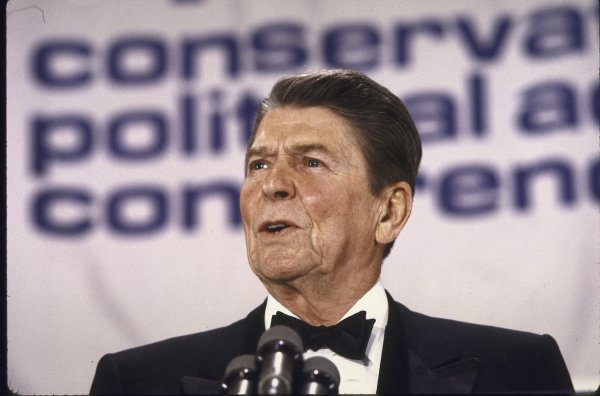

Ronald Reagan would have disagreed. He believed as much as anyone in a conservatism grounded in eternal principles. But he also believed that principles were the enemy of ideology. In his speech to the 1977 CPAC convention, Reagan noted that an overly dogmatic ideology begets “a rigid, irrational clinging to abstract theory in the face of reality.” American conservatism, he said, was “free from slavish devotion to abstraction” and possessed a “willingness to learn” from experience.

Today, experience teaches us that a majority of Americans are hurting. Some are hurting economically, buffeted by the deindustrialization of America that proceeded at warp speed after China entered the World Trade Organization. Some are hurting culturally, rightly feeling their way of life is under assault from an educated, urban tribe that views them as backwards and troglodyte. Others live in fear for their safety, whether from crime in their neighborhood or from terrorists who seem to strike when and where they want. A conservative who can learn from experience, then, would try to reach these people where they live and bring them into the conservative tent.

That is exactly what conservative populism aims to do. It is in theory no different a project from that which Reagan embarked upon when he sought to bring what would become the “Reagan Democrats” into the Republican Party. Back then, Reagan noted that “conservatism can and does mean different things to those who call themselves conservative.” Bringing different types of conservatives into one big tent required compromise—not compromise of principle, but compromise over the specific policies that would be pursued at any given point in time.

Some modern conservatives would say that the compromises required to create a new Republican Party would be compromises of principle. For these people, any expansion of federal government power, any attempt to alleviate suffering through government action, is a violation of conservative principle. Thus, Trump’s tariffs are wrong; Trump’s opposition to cutting entitlement programs must be overcome; Trump’s support for government-financed paid family leave must be defeated.

Reagan had a word for conservatives like this: “ultras.” These conservatives were people who “jump off the cliff with flags flying” rather than “take what [they] could get.” Throughout his career he faced challenges from conservatives who said he was giving in and adapting too much. He always stared them down, got what he wanted, and retained the adoration of rank-and-file conservatives. There’s a lesson in there for today’s would-be ultras.

Today’s conservative movement has already quietly adapted from its staunch libertarian roots. Instead of pledging to undo the New Deal and to “stand athwart the tide of History, yelling ‘Stop’!”, today’s movement is content to slow the growth of government and introduce market elements into the workings of government. There’s nothing in that new legacy that forbids or even retards further adaptation in order to preserve the most important elements of the American way of life, personal and political liberty.

That was Ronald Reagan’s belief. He worked tirelessly to make the Republican Party into “the party of working people.” Indeed, at the end of his career, when he was campaigning for George H.W. Bush in October, 1988, he let the cat out of the bag. Speaking before a group of Italian Americans on Columbus Day, Reagan said:

Let me take a moment to tell you something I’ve never said before. You know I’m a former Democrat. And it’s often said that the once-proud Democratic Party of F.D.R. and Harry Truman is dead and gone; that the Democratic Party has been taken over by the left; that the departure from the mainstream that we began to see at their 1968 convention now defines the party at the national level, especially the liberal leadership in Congress. But there’s something you should know.

The party of F.D.R. and Harry Truman couldn’t be killed. The party that represents people like you and me, that represents the majority of Americans—this party hasn’t disappeared. The fact is we’re stronger than ever. You see, the secret is that when the left took over the Democratic Party, we took over the Republican Party.

That was the Gipper’s dream, to take the best of the old Democratic Party and make it into the new Republican Party. That, not Barry Goldwater’s neo-libertarianism, is the conservative movement’s true legacy.

Living up to that legacy today requires prudence and statesmanship. It requires bringing in new voters who don’t always agree eye-to-eye with the existing conservative movement. It requires populist conservatism.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

America’s future turns on an iron hinge.

Liberalism, pluralism, and self-government are indeed under threat.

The new movement in American politics is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.