In its effects, it is synonymous with liberalism.

The Telos of the American Regime

Conservative jurisprudence grapples with a new view of Originalism.

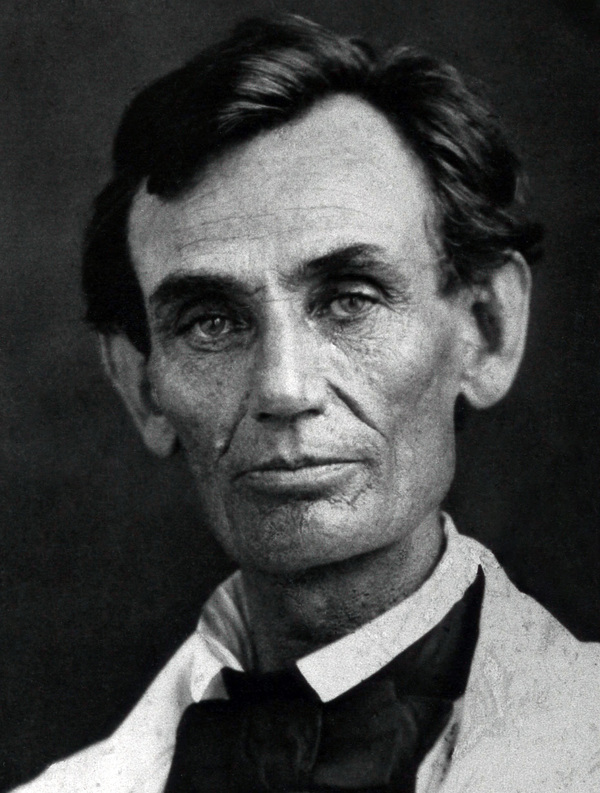

There is nothing new about struggles over the soul of jurisprudence on the Right. Harry Jaffa advanced moralistic constitutionalism against positivism in running debates with legal titans such as Antonin Scalia and Robert Bork. Remarkably similar themes undergirded Abraham Lincoln’s 1858 grapples with Stephen Douglas. Today’s recapitulation of these conflicts, however, break important new political ground. In 2021, the future of the Right as a coherent governing movement turns, in no small part, on recognizing the jurisprudential failures of the conservative establishment. Only a fresh articulation of a moral originalism can lead the Right back from this institutionalized defeat.

Toward that end, I recently debated Ed Whelan on “common good originalism”—a jurisprudential framework first outlined here at The American Mind—as part of The Heritage Foundation’s “Judicial Clerkship Training Academy.” The in-person debate followed Whelan’s response to my most recent writing on common good originalism, as well as a rebuttal from National Review’s Dan McLaughlin and an exchange with the Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro on the topic.

Around the same time, The American Mind published “A Better Originalism,” the lengthy jurisprudential manifesto that my co-authors styled “an appeal to conservatives for an originalism of moral substance.” We concluded our fusillade across the bow with a friendly call “to break away from a jurisprudence that has underserved and underwhelmed—both practically and morally—and diminished our understanding of the proper ends of the law.” Those substantive ends are the ineffable truths embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the American regime’s telos, most clearly expressed in the Constitution’s common good-oriented Preamble—the Founders’ most overt explanation of whither we are going. “A Better Originalism,” much like common good originalism, elicited some skeptical (to put it mildly) responses from the self-anointed positivist/libertarian gatekeepers of the embedded Originalism, Inc. (and Fusionism, Inc.) establishment.

From Twitter DMs to Clubhouse chats, conservative jurisprudence has not attracted this level of enthusiasm in years. The energy coincides with eminent natural law philosopher John Finnis’s recent First Things essay on the unconstitutionality of abortion—thus revitalizing a long-simmering dispute in conservative circles that had most recently been fleshed out in academic form a few years prior by Josh Craddock, then-editor of the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy (JLPP). Whelan and like-minded positivists have responded to this specific debate in predictable fashion, thus setting in motion a further series of notable Twitter recriminations between Originalism, Inc. and its myriad ascendant detractors. Craddock has been explicit in tracing the thread of abortion-related jurisprudence to the fundamental struggles for America’s regime. “As a matter of political morality,” he wrote, “the states-rights view on abortion is nothing other than an echo of Stephen Douglas’s arguments.” Indeed, Finnis versus Whelan on abortion echoes Lincoln versus Douglas, just as it reflects Ahmari versus French today.

All of these various lines of legal and political disputation intersect with and reinforce one another. A realignment is unfolding before our eyes right now in American politics—something The American Mind and the Claremont Institute, to their great credit, both advance and reflect. The key question is whether the Right will continue its philosophical deliberalization toward a more prudential balancing of individual liberty maximalism with the more common good-oriented telos of the American regime. Will conservatives, in other words, become truly comfortable “wielding ‘regime-level’ power in the service of good political order,” as it pertains to such foes as Big Tech oligarchs, in order to “reward friends and punish enemies (within the confines of the rule of law)?” The prudential pursuit and application of political justice, to speak Aristotelian, form the backbone of the “new Right,” “national conservatism,” “common good conservatism,” or whatever we prefer to call our more liberalism-skeptical, genuinely political movement.

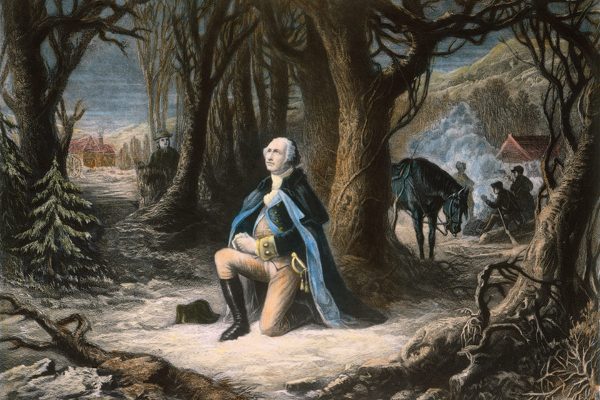

The point is that we side unwaveringly with Lincoln over Douglas—with the statesman’s hierarchical prioritization of substantive justice and the commonweal over a morally denuded, “neutral” proceduralism. Judges have a distinct (if limited, as a matter of allocative power) role to play here. As we say in “A Better Originalism,” “the act of judging necessarily involves treating law as a teacher of our fellow citizens. To teach in a modest way, judges should embrace their role as a co-equal branch to articulate the first principles of moral and legal judgment.”

Our critics are mistaken when they proffer Hamilton’s famous “judicial restraint” plea in Federalist #78—that our judges should “have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment”—as a sort of slick “gotcha.” Not only would Hamilton himself personally agree with our common good-oriented reclaiming of the American regime’s telos, as a matter of both jurisprudence and economics, but the very act itself of rendering legitimate judgments requires an awareness and appreciation of the overarching substantive regime orientation to which those ad hoc judgments must necessarily point. The statute and the judicial decree are both necessarily subservient to the telos of the regime, as expressed in our Founding documents. The lack of precisely such an awareness and appreciation for our telos was, among other methodological shortcomings, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s folly in the lamentable Bostock decision from last year.

Our overly liberalized, overly positivist, and overly lawyered friends remain obstinately attached to their blinders, which preclude them from considering the full purview of both the historical empiricist tradition and the eternal/transcendental alike. Oren Cass calls the hands-off economic policy paradigm of market/private-sector fundamentalism “Let the Market Rip”—in contrast to the implicit Two Cheers for Capitalism of “Planning for When the Market Cannot”—and one can similarly contrast a hands-off legal paradigm of “Let Legal Positivism Rip” with the imperative to assertively and unapologetically channel the telos of the American regime “When the Positivist Law Cannot.” When we boil it down to the mechanical nuts and bolts—something that will become clearer in my upcoming JLPP article—this is all Preamble-heavy common good originalism and the closely related moralistic methodology we outlined in “A Better Originalism” actually do. But just as the doctrinaire libertarians cannot remove their economic blinders and reconsider the craft of economic policymaking, so too are the doctrinaire legal positivists incapable of removing their own blinders and reconsidering the craft of judicial statesmanship.

Perhaps the most thorough response to “A Better Originalism” thus far has come from John G. Grove, associate editor of Law & Liberty. Grove scores some clever points in his favor, especially with respect to the Constitutional Convention’s Committee on Style, which drafted the Preamble without leaving behind any notes or recorded debate, but much of his line of argumentation is simply redolent of the Scalia and Bork oeuvres.

At other times, Grove outright misses the mark. He posits that such interpretive mechanisms as the “construction zone”—which sets the plausible boundaries for a given provision—“cannot authorize the importation by judges of moral content…on which the Constitution is not indeterminate but utterly silent.” But that begs the very question it raises—for instance, in the case of Finnis and Craddock on the unconstitutionality of abortion, the entire debate is whether the Constitution is actually silent on the matter if it is properly understood and construed. Grove furthermore chastises us for our “rejection” of the “moral timidity” of the great statesman Edmund Burke—a rather curious charge, given that our statement is exclusively focused on jurisprudence and Burke’s views on such jurisprudential topics as precedent and stare decisis were hardly what cursory armchair historians (such as Chief Justice John Roberts) might expect them to be based, for example, on the political themes of Reflections on the Revolution in France.

The conservative grassroots intuits that, across our political and legal life, something more is needed than sclerotic or cobwebbed positivist pieties. We need more common good and more of a “consolidationist” political and legal agenda. We are “drowning” in the economic and cultural excesses of post-World War II neoliberalism—starving for an economic and cultural life that fosters human flourishing and the good life. The old guard willfully turns a blind eye to questions of what, in this sense, modern conservatives have been able to “conserve” of the foundations of our flourishing. Their task will be difficult: Not only does the new guard have the momentum. We also have the telos of the American regime and the American way of life on our side.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

More than abstraction is at stake.

Political prudence requires reason—which is why a "conservative rationalism" that embraces universals and particulars alike is needed now more than ever.